WRITTEN BY KATE FINAN, CO-OWNER OF BOOM BOX POST

One of the biggest challenges in sound design is creating unique and beautiful design work that will work with the musical score rather than against it. Because television schedules are tight, composers often need absolutely every moment they can get, and the music goes directly to the mix stage without the sound design team ever hearing it. In a dream world, we would be constantly collaborating with the composers and music departments. But unfortunately, we’re often on two secluded islands, trying to create something fantastic on our own, and just hoping that it will work when it’s all put together in the mix.

As I get more and more experience as the re-recording mixer, I’ve come to intuitively understand what will work and what will never work in a sound design build once the music is added, no matter how cool it sounds in the sound effects preview.

The key to designing sound that will work flawlessly with any musical score hinges greatly on the use of inharmonic elements rather than harmonic ones. But to understand what will work and when, we need to dive deep into the concept of harmonic versus inharmonic elements.

The Difference Between a Sound Effect and a Musical Element

All sounds have a pitch, but sound effects in general, such as a jackhammer or a door slam for example, contain elements which vary so greatly in pitch over time or have so many different pitches simultaneously that any particular pitch is imperceptible. Basically, the human brain can’t weed through all of the information that the ear is receiving to decide what the pitch is. These sound effects of everyday items always work well with the score.

Harmonic Versus Inharmonic Musical Elements

We get into a murky mixture of sound design and music when we need to incorporate musical elements into a build without knowing the key or chord structure of the score at that given moment. Some examples might be a magical moment where we want to cover a pixie dust swirl, a heavenly light shining down on a character that gives us the quintessential “ahhh” feeling, a pulsating laser beam that begs for an oscillating sine wave, etc.

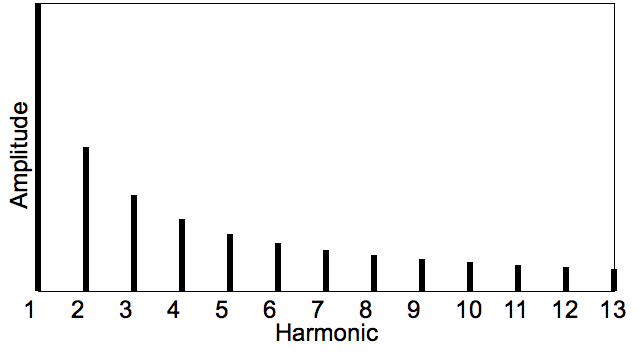

So, it’s important to understand harmonic versus inharmonic elements and where each instrument falls on that scale. Musical instruments which can be perceived to have an exact pitch are perceived thusly because the overtones above the fundamental pitch are exact integer multiples. Standard musical instruments which create their sound with a string, wire, or column of air (such as a guitar, a piano, or a clarinet) are harmonic instruments. If you’re not sure, just ask yourself if that instrument can play a melody. If so, it’s a harmonic instrument. These instruments should be avoided at all costs during sound design because you will never be able to divine the exact pitch of the music at that moment and they will without a doubt clash and need to be removed.

In contrast, instruments which cannot play a melody have overtones that do not exactly lie on integer multiples and therefore have a tonal structure which makes it difficult for our ear to distinguish the frequency of the sound. Most often, these are percussion instruments such as the tam-tams, chimes, cymbals, or gongs. These are always a great choice for sound design as they will lie on top of any music perfectly and act as sweeteners.

Understanding the Spectrum of Inharmonicity

Harmonic

As mentioned above, any musical instrument with exact integer overtones over the fundamental (perceived) pitch is harmonic. This category includes all non-percussion orchestral instruments such as the oboe, bowed violin, and french horn. These should be avoided during sound design as they will not play well with any underscore.

The oboe, bowed violin, and french horn are all examples of harmonic instruments.

Nearly Harmonic

However, there are some instruments which lie in the middle of this spectrum. Plucked string instruments such as the guitar, harpsichord, and harp are often considered nearly harmonic. In my opinion, these never work in a sound design if there will be score under because although the timbre is a bit more murky than with a purely harmonic instrument such as the flute (think about the hammer-like quality of harpsichord versus the pure tonal timbre of the flute), they still play a perceived note and you would need to know the proper chord playing in the music. For this reason, I almost never employ harp glisses in my sound design build unless specifically asked by clients. Even then, I let them know it likely will not work and I’ll add a similar but inharmonic option, like a chimes glissando.

Approximately Harmonic

Tuned percussion instruments such as the tablas, timpani, marimba, and xylophone are considered to be approximately harmonic. These instruments are less harmonic than the nearly harmonic instruments, but they can still carry a melody. This proximity to inharmonicity makes them prime candidates for short and simple sound design builds which beg for a musical element. A timpani boing can be used without worrying too much about clashing with score as long as it’s an isolated moment and not continuing throughout a whole scene (that, in my opinion, would get tiresome and start to be perceived as clashing as it combined with the different chord changes of a musical cue). A xylophone trill can cover a finger twirling motion with little anxiety from the sound designer. A single marimba hit could convey an eye blink. But, with all tuned elements, these are still somewhat risky and may need to be removed if they are particularly at odds with the score.

Xylophone, marimba, and tablas are all examples of approximately harmonic instruments.

Completely Inharmonic

Finally, untuned percussion instruments are considered to be completely inharmonic. Untuned/unpitched percussion instruments are often referred to as auxiliary percussion instruments in an orchestra. These instruments are used to provide a rhythm or accent to the music without contributing any melody. The fact that they do not produce a recognizable single pitch does not mean that they do not need to be tuned (such as a snare drum) or have a perceived pitch when played in isolation (like a pea whistle or siren). This category of instruments, which you can use with free rein, includes nearly all cymbals, most drums, and all rattles, maracas, and cowbells.

A snare drum, cymbals, maracas, and cowbells are all examples of inharmonic musical elements and can be used freely without worrying about clashing with music.

Examples of Great Inharmonic Sound Design Choices

I know that all of this seems very technical, but I promise that having this base knowledge will pay dividends in ensuring that your work plays in the mix. So, let’s look at a few real world examples.

In the past, I’ve had a client who loved to employ high-suspense orchestral stings to amp up the anticipation. Ideally, these would be done by the composer, but it was not their strong suit. So, they created a sting, but I was asked to create my own stings at key moments which could be used to sweeten the musical sting or as a standalone without music if the music really wasn’t cutting it. In short, they needed to have a lot of oomph but also play well with others. In this scenario, and example of what I might create would be a reversed cymbal swell plus rising windy whoosh leading into an apex composed of a taiko drum hit plus castle door slam.

Another example would be a magical swirl of pixie dust. For this, I would use a series of chime glissandos (aka glisses), bowed cymbals, cymbal swells, whooshes, and sparklers for added crackling texture. The chimes give the “pixie dust” feel, the sparklers add a bursting texture, and the cymbals make it all feel musical without actually interfering with the score.

A final example would be a pulsating ray gun beam. Using a sine wave for this will result in a perceived pitch which inevitably won’t work with the music. However, you can start with a sine wave, then use an LFO to oscillate it, and add some distortion in order to muddy the pitch. This more “fuzzy” version of a sound will not clash with musical elements in the same way that a pure wave would. The more you modulate and introduce additional overtones that are not at a constant or regular frequency, the easier it is for a sci-fi sound to live in the mix as a sound effect that isn’t perceived to interfere with the music.

Additional Reading

This is a highly technical topic, but really does pay dividends if you take the time to understand it. For additional information, check out these other sources.

Unpitched Percussion Wikipedia

Bart Hopkin’s Overtones Harmonic and Inharmonic

Bart Hopkin’s The Territory Between Clear Pitch and Pure Noise