WRITTEN BY KATE FINAN, CO-OWNER OF BOOM BOX POST

I recently began work on a new show, and luckily it has already presented tons of new challenges. At Boom Box Post, we like to consider sound design challenges as creative opportunities. So, when I spotted an episode in which the characters travel via microscopic submarine through a human body, I was excited. Each exterior shot of the submarine illustrated it moving through a viscous plasma-like liquid. I wanted to call upon the tried and true sounds of a submarine for the vehicle itself, but I wanted to do something unique for the sound of it moving through the plasma. This was the perfect opportunity to get creative with some recording!

This presented an immediate challenge: we do not own a hydrophone. I looked into buying one, but they are somewhat expensive and our underwater recording needs are pretty slim. It didn't seem worth the investment. I considered using one of my current mics and wrapping it in a water-proof casing, but that struck me as pretty risky. So, I settled on buying a couple of inexpensive contact mics, a pack of condoms to act as water-proofing, and some heavy duty duct tape to put it together.

About Contact Mics

If you've never used a contact microphone before, they are wonderful things. Sometimes called piezo (pronounced pee-EH-zo) mics, they are what is used for the pickups on electric guitars. You can buy them as a standalone version, and either tape them to the object you are recording or use the adhesive on the mic itself, thus turning any everyday object into an electric whatever (i.e. electric cello, electric rainstick--the possibilities are endless!) But, keep in mind that they work differently than all of the other microphones in your mic locker. Normal microphones pick up subtle changes in air pressure as an audio wave passes the microphone. Conversely, contact mics pick up the vibrations of physical matter and transduce those vibrations into an electric signal which can be transduced again into audio.

Thus, contact microphones have no sensitivity to the audio waves passing through the air. This makes them very unique as recording devices (and sound designer tools!) because you don't need to worry about ambient noise that must be removed later. A great example of this is that if you were to, say, turn on an electric beard trimmer and skim it across the surface of a cymbal, a traditional microphone you would pick up not only the awesome sound of metal on metal, but also the whir of the trimmer's electric motor. If you,instead placed a contact mic on the surface of the cymbal, you would only pick up the sound of the trimmer skimming the metal cymbal, because it does not transduce sound waves traveling through air, only those through the physical object itself.

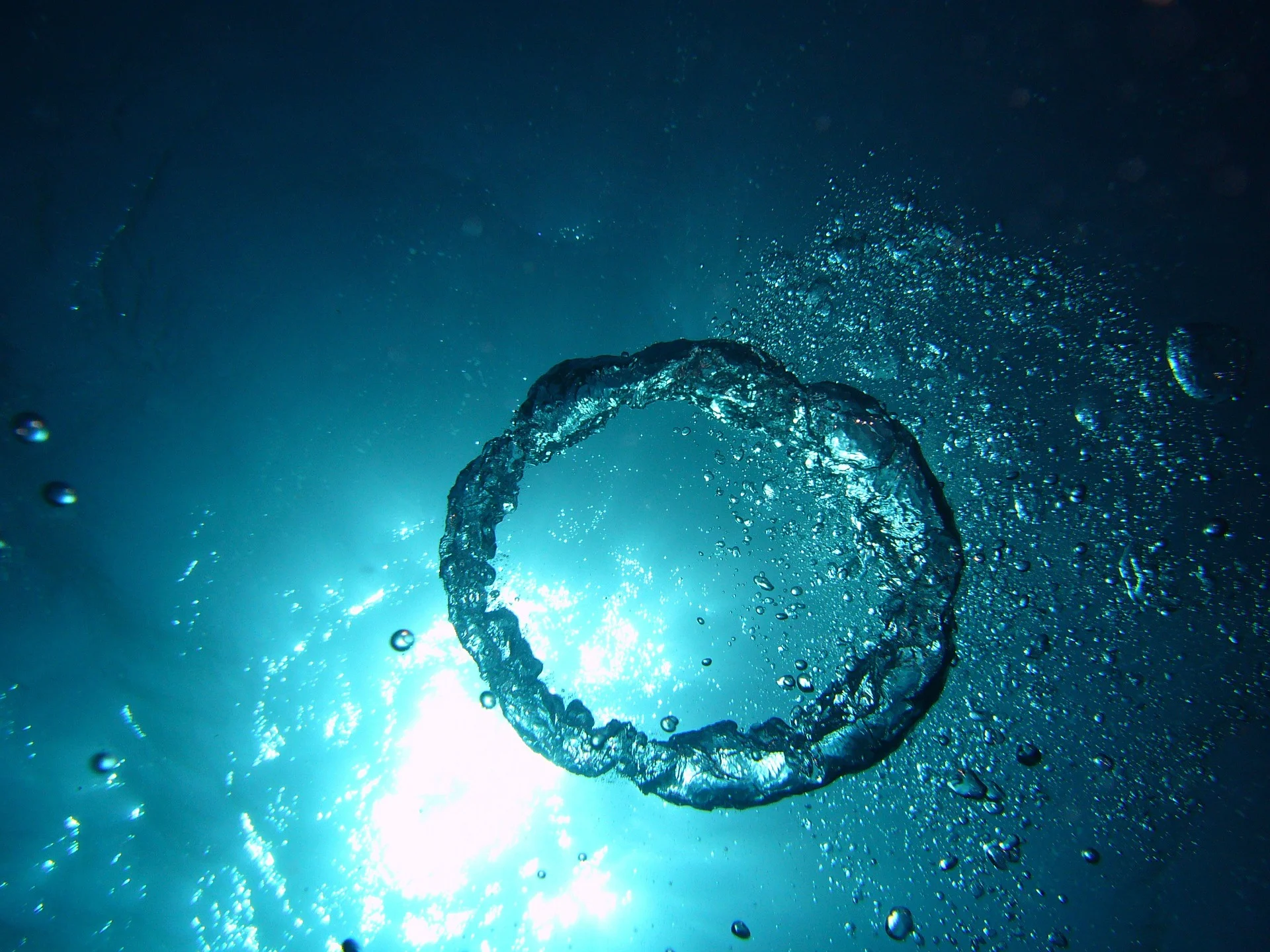

Now, would this particular technology lend itself to recording underwater? That was a tough call. Would the pressure differences in the water as the mic moved through itbe extreme enough for the contact mic to pick up the physical change? I acquired all of the necessary parts: contact mic, tape, condom (for water-proofing), recorder, and headphones, and then filled a small metal tub with water to find out.

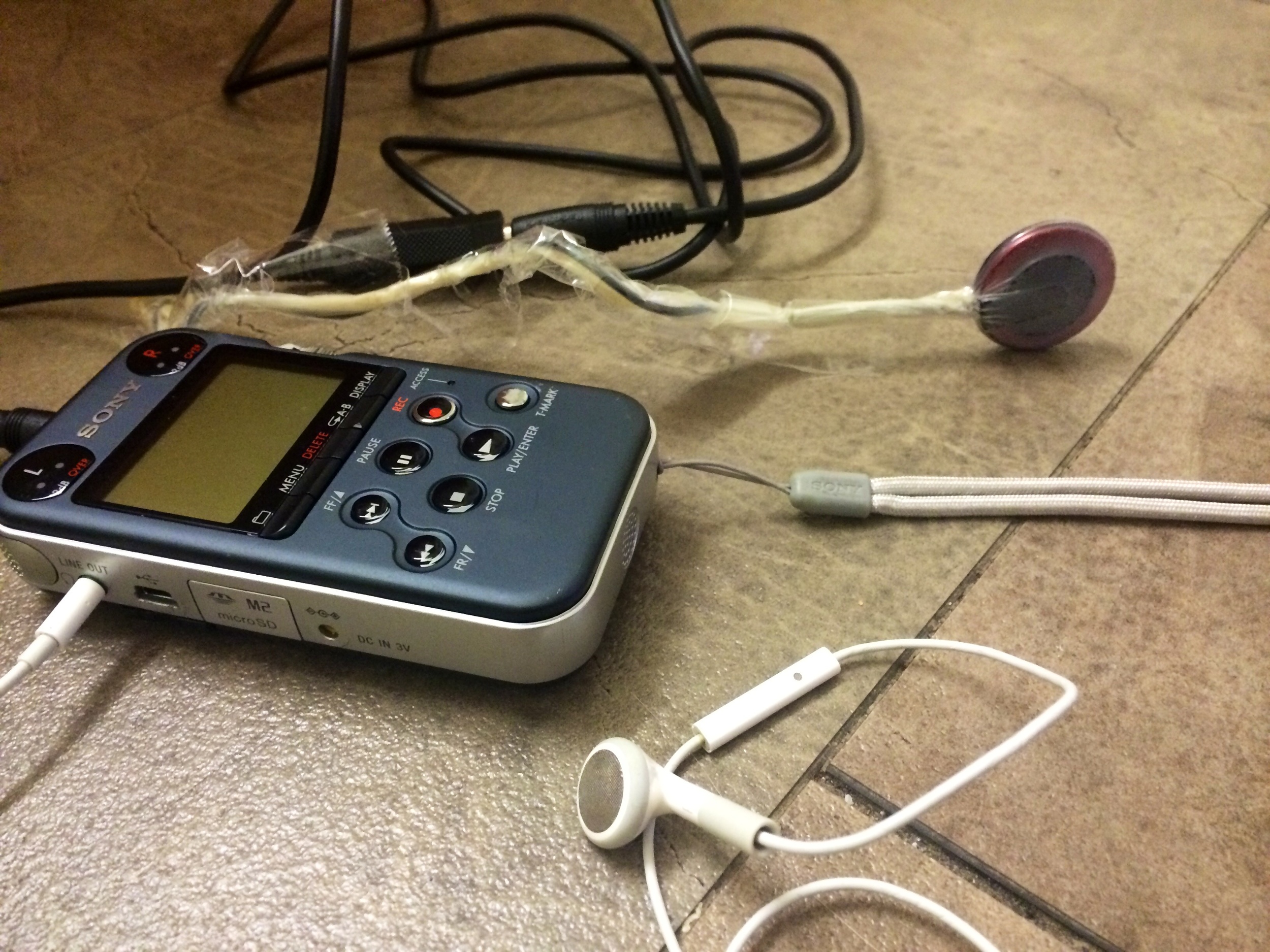

My underwater recording equipment.

My trial attempt in the metal basin.

The Trial Run

I learned a lot from this initial experiment. Dragging the submerged contact mic through the water did not result in any audio. However, turning on the faucet and letting the water hit the contact mic did. Unfortunately, that audio did not have the sound that I was looking for. It was crackly (think: rain drops landing with hard splats on a plastic surface), not watery. From there, I tried submerging the microphone near the point of entry of the running water and found that I got a great bubbly sound. The water pressure was changing constantly as the faucet poured into the basin, but I wasn't getting the hard hits of the water slamming against the mic itself. I brought those sounds into ProTools, and while they were definitely in the vein of what I wanted, the size just wasn't there. They sounded too small.

The Final Record Session

So, I took the recorder home and did my final session in my home bath tub. I submerged the mic and recorded steadies at the point of entry of the water, and then ran the mic back and forth over that area for the submarine bys. The contact mic, being that it records physical vibrations, picked up fabulously unique splatty sounds for these--just what I was looking for!

The final recording session in my home bath tub. The angle is not great, but I was trying not to drop my camera, recorder, or the microphone into the water.

My final record session setup. I settled on using clear mailing tape to stretch the condom over the cable for ease of use.

Editing the Material

I brought everything into ProTools again, and then was faced with an additional technical issue inherent to almost all contact mics. Because they consist of small capicators in series, they function at a much higher impedance than a regular microphone. When connected to a typical line input, this creates a high pass filter, thus cutting out any low end from your recordings. I was aware of this issue, and had set up my session with this in mind. I separated the files I wanted to work with, then ran them through a low-pass filter EQ, pitched them down an octave, and also applied both tactics to each file to see which approach brought the sounds closest to what I was looking for. In the end, I bounced some of each . Here are a few samples:

The Sounds

I used this rumble for one of the background elements when we are on the exterior of the submarine. It gives a great low-end weight to the underwater scene:

This file is also one of the background elements that I created. It adds a certain squishy feel that makes us feel like we're looking through viscous plasma:

Finally, these are a few of the "bys" that I created for the submarine moving through the dense liquid. The really splatty ones work extemely well since the submarine has thrusters and needs to sound very energized. These sounds help to make it feel like an underwater rocket ship. I made short, long, low, and high versions of these: